The Kabbalah, the Tarot and the Middle Way

Kenneth Chan

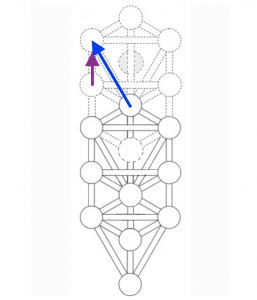

14. Reaching for Briah

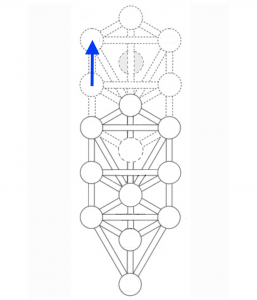

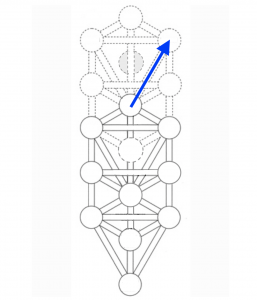

The door to Briah that needs to be opened is found on the path between Chokmah and Binah. It is the threshold that needs to be crossed before we can make the journey into this higher World of Manifestation at Briah. In order to reach this door, we need to develop sufficiently the two Sephiroth, Chokmah and Binah. Essentially, we need to transform Hod into Binah, and Netzach into Chokmah. This is a similar process to that required to reach the World of Yetzirah from that of the World of Assiyah.

In a corresponding way (to that found in reaching for Yetzirah from Assiyah), when Hod in Yetzirah has been transformed into Binah, Binah will function as the new Hod in Briah. And similarly, when Netzach in Yetzirah has been transformed into Chokmah, Chokmah will function as the new Netzach in Briah.

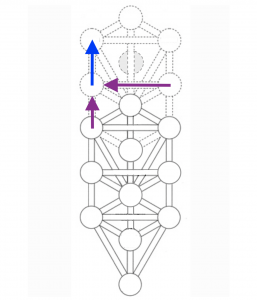

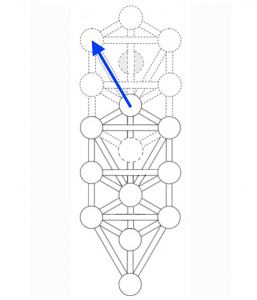

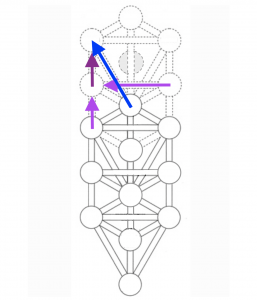

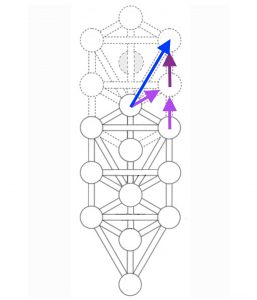

This process is achieved through the four paths from Geburah to Binah, from Chesed to Chokmah, and from Tiphareth to Binah and to Chokmah. In a corresponding way to that found in the world of Assiyah, the path from Geburah to Binah, when sufficiently developed, will bring forth the path from Tiphareth to Binah. Likewise, the path from Chesed to Chokmah, when sufficiently developed will bring forth the path from Tiphareth to Chokmah. These paths function and interact in the world of Yetzirah in the same way as the corresponding paths in the world of Assiyah. It is as stated in the hermetic text: “as above, so below.”

The two vertical paths on the left and right pillars (i.e., from Geburah to Binah and from Chesed to Chokmah) essentially constitute the process of transforming our mind to one that is suitable and capable of receiving the spiritual insight and motivation that comes from Tiphareth. It is the process of making the mind receptive to the inspirational realization, which otherwise would be like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

Let us look first at the path from Geburah to Binah, which is depicted by the Tarot card, The Chariot:

YETZIRAH: Geburah – Binah

Tarot: The Chariot

This path is the culmination of the influences from the two paths leading to it—from Chesed to Geburah and from Hod to Geburah. Thus it is the combination of the effects from the practice of exchanging self for others, and from the process of attaining a closer union with the All through the clearing of karma. This combination leads to a transformation of our being to one that now focuses on striving to act for the benefit of all without even the thought of there being a self.

This is represented in the Tarot card, the Chariot, which depicts a conscious effort, a drive, to achieve the goal of acting with a mind in a state of nonduality, and in particular, without the duality of self and others. The chariot is drawn by a black and a white creature, in combination, representing the process of bringing together the elements that form a duality in our thinking.

This path is at a stage beyond that of exchanging self for others. Here, there is no longer even the thought of a separate self and others. The welfare of all becomes the reference perspective upon which our motivation and actions are based. The purpose of our motives and actions now naturally targets the welfare of all. This is one crucial sense of nonduality. The chariot thus represents the conscious drive to work for the benefit of all sentient beings without the sense of a separation between the self and others.

When this the path, on the Left Pillar of the Tree of Life, is sufficiently developed, and our mind has become sufficiently receptive, it will draw forth the experiential insight represented by the path from Tiphareth to Binah (in the same way the two corresponding paths interacted in the Tree of Life in Assiyah).

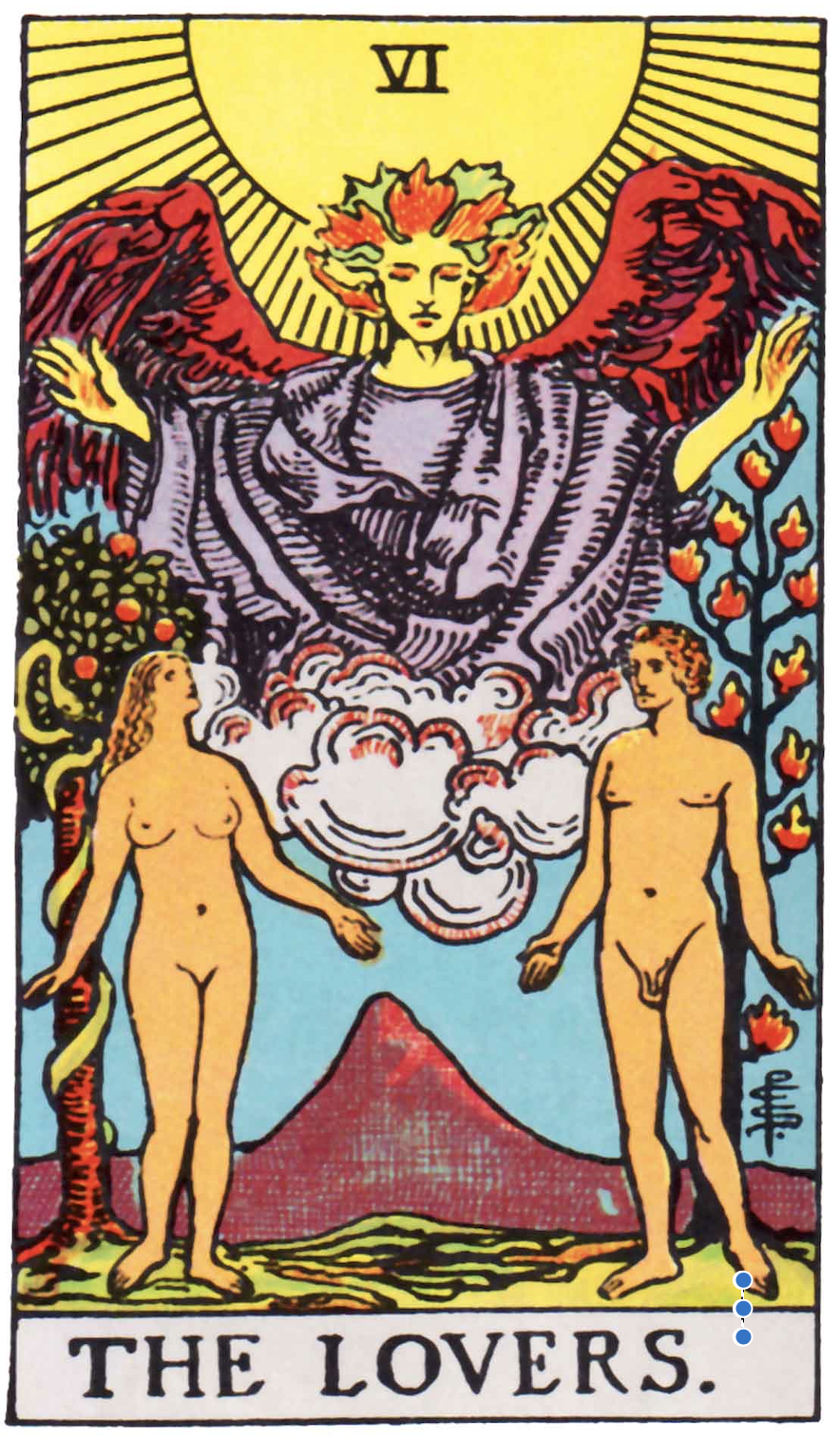

The path from Tiphareth to Binah is depicted by the Tarot card, The Lovers, and by the Noble Eightfold Path as Right Meditation.

YETZIRAH: Tiphareth – Binah

Tarot Card: The Lovers

Noble Eightfold Path: Right Meditation

The Lovers, depicted in the Tarot Image, represent a union. It is the realization of nonduality, and a realization that stems from the divine source, that comes through Tiphareth. The Tarot image shows the Lovers being given the blessing from an angel above, which represents the fact that this realization comes from above.

The Lovers represent a realization of nonduality that is of a broader scope than that of the Chariot, which depicts the path from Geburah to Binah. That path is brought about by the conscious decision not to differentiate between self and others. This is an important aspect of nonduality. With this modification to our mindset, we make our mind more receptive to the realization of nonduality in general. And so, with the divine inspiration that resides in our Buddha nature, that reaches us through Tiphareth, we gain the correct meditational or mystical experiential understanding of nonduality, represented here by the path from Tiphareth to Binah.

This process, of first making our mind more receptive in order to gain new spiritual realizations, is akin to the process we had observed in how the path between Netzach and Chesed prepares us to receive the spiritual insight found in the subsequent path between Chesed and Chokmah. Recall that the path from Netzach to Chesed removes the realizational obstacles that stem from our self-cherishing that is innate in greed, hatred, jealousy, etc. When these obstacles are removed, we are then ready for the path from Chesed to Chokmah which represents the initial realization that the self is empty of inherent existence.

After deepening the realization that the self is empty of inherent existence, this realizational process is continued further here in Yetzirah. Here, the path depicted by The Chariot (from Geburah to Binah), which represents the realization of the nonduality between self and others, brings forth the path depicted by The Lovers (from Tiphareth to Binah), which represents the realization of the more general nonduality of all phenomena. And in abiding by the words of the Hermetic text—“as above, so below”—it is akin to the same process where the path between Geburah and Binah in Assiyah, prepares our mind to receive the realization on the path between Tiphareth and Binah in Assiyah.

An essential part of the realization of nonduality is that which results from dispelling the dichotomy between self and others. But nonduality refers to many other aspects of reality as well. When we have gained adequate realization of the nonduality between the self and others, our mind will be ready to receive the realization of other aspects of nonduality. Note that the state of duality is represented in a number Tarot images by two vertical pillars, and the realization of nonduality is represented by the middle path that goes between these two pillars.

______________________________________

Here we shall discuss briefly two of the other important aspects of nonduality: The nonduality of mind and matter, and the nonduality of existence and nonexistence.

The Nonduality of Mind and Matter

One aspect of nonduality that needs to be realized on the spiritual path is the nonduality of mind and matter. This duality of mind and matter is particularly deeply imbedded in Western philosophy, and it has unfortunately also been largely adopted by the mainstream science community. Because of this prevalent way of thinking, we tend to divide the reality before us into objective and subjective elements. This tendency is actually an artificiality imputed by the mind and does not exist in nature. There is no scientific evidence for this mind-matter dichotomy. Actually, the reverse is true. The scientific evidence provides evidence that there is, in fact, no duality of mind and matter, because this mind-matter dichotomy is incompatible with quantum mechanics.

It is because of the insistence on this philosophical stance of a mind-matter duality that physicists have failed, for more than a century now, to adequately explain the scientific findings of quantum physics. Even today, there are numerous competing interpretations of quantum mechanics. The very fact that there are so many different interpretations means that none of them are actually free of conceptual problems. If one of these interpretations cannot be faulted, this one interpretation would have replaced all the others. But this has not occurred. Physics Nobel laureate, Richard Feynman, correctly states that nobody understands quantum physics. The reason for this failure in understanding quantum physics is simply the fact that it is impossible to explain quantum mechanics in terms of a mind-matter duality.

Note that two of the pioneers in creating quantum mechanics, Werner Heisenberg and Wolfgang Pauli, in the later part of their lives, essentially came to the same conclusion. In the words of Werner Heisenberg:

“The physicist Wolfgang Pauli once spoke of two limiting conceptions, both of which have been extraordinary fruitful in the history of human thought, although no genuine reality corresponds to them. At one extreme is the idea of an objective world, pursuing its regular course in space and time, independently of any kind of observing subject; this has been the guiding image of modern science. At the other extreme is the idea of a subject, mystically experiencing the unity of the world and no longer confronted by an object or by any objective world; this has been the guiding image of Asian mysticism. Our thinking moves somewhere in the middle, between these two limiting conceptions; we should maintain the tension resulting from these two opposites.”

We are not sure which form of Asian mysticism Heisenberg was referring to in the quote, but it appears that he was, unfortunately, unaware of the important Eastern philosophy whose name can literally be translated as the “Middle Way”—namely, Madhyamika philosophy. There is no mind-matter dichotomy in Madhyamika philosophy.

Essentially, quantum mechanics shows us that all phenomena are dependently arisen. And it is the experiential event which, in our dualistic language, would be the mind’s direct perception of the object (without further distorting elaborations) that is the primary reality. There is no mind-matter duality in this primary reality of the experiential event. It is only because of the limitations of our language (that caters to this dualistic thinking) that makes it appear as though mind and matter were separate. But the primary reality of the experiential event, as depicted by quantum mechanics, has no such duality. A direct realization and perception of this nonduality is, in the terminology of Dzogchen, what is known as rigpa, the pure awareness that is free of distorting elaborations and imputations. (For a more detailed analysis of how quantum mechanics demonstrates the nonduality of mind and matter, see A Direct Experiential Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics.)

This tendency for us to divide the world into objective and subjective elements is one of the factors preventing us from experiencing sunyata. The word tathata, which is the experience of sunyata (which refers to the experience of reality when we attain a direct realization of emptiness), is often translated as “suchness” or “thatness,” meaning to say that what we have before us is simply what it is, without all these artificial elaborations we project upon the world we experience. There is no reason to divide what we have before us into “objective” and “subjective” elements as though there really is a mind-matter dichotomy. This mind-matter duality is merely an imputation of the mind and does not really exist, and quantum mechanics is directly telling us that this is the case. Unfortunately, this idea of a mind-matter duality has become so ingrained in our culture that many find it extremely difficult to envisage a world without this artificial concept, and physicists still insist on trying to fit their scientific evidence into this erroneous scheme of things even after failing to do so for more than a century!

This deeply ingrained nature of our mundane dualistic thinking is the reason why there is the need for us to sufficiently transform Hod into Binah (in Yetzirah) through a transformation of our core reference perspective, before our mind can be receptive to the experiential insight of nonduality that comes from Tiphareth. Otherwise the realization, represented by the path from Tiphareth to Binah, cannot be received. It would be like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole.

______________________________________

Another aspect of nonduality that we will come to realize on the path from Tiphareth to Binah (in Yetzirah) is the nonduality of existence and nonexistence.

The Nonduality of Existence and Nonexistence

[Note to readers: This is a difficult section to fully comprehend. It is included here for the sake of completeness. A full comprehension of what is explained here, however, is not absolutely needed for the understanding of the subsequent sections of this paper. So, it is fine to proceed reading the subsequent sections without having fully understood what is explained here with regards to the nonduality of existence and nonexistence.]

The crucial aspect of nonduality in Madhyamika philosophy is the nonduality, between existence and nonexistence, in the things that we perceive. In other words, all things are neither essentially existent nor essentially nonexistent. That is the central principle and the reason why Madhyamika philosophy is also known as the middle way philosophy. It takes the middle way between these two extremes—the extreme of existence and the extreme of nonexistence.

A good way of understanding this nonduality of existence and nonexistence is by looking at the explanation, of the famous tetralemma (found in Buddhism), provided by Tsongkhapa (the founder of the Gelug tradition of Tibetan Buddhism that is now headed by the Dalai Lama). Tsongkhapa presents this explanation in the Lam Rim Chen Mo in the form of an objection (qualm) that he then addresses (reply):

Qualm: The Madhyamaka texts refute all four parts of the tetralemma—a thing or intrinsic nature (1) exists, (2) does not exist, (3) both exists and does not exist, and (4) neither exists nor does not exist. Reason refutes everything as there are no phenomena that are not included among these four.

Reply: As indicated earlier, “thing” has two meanings. Between these two we refute the assertion that things essentially exist in terms of both truths [i.e., the ultimate truth and the conventional truth]; however, at the conventional level we do not refute things that can perform functions. As for non-things, if you hold that non-compounded phenomena are essentially existent non-things, then we also refute such non-things. We likewise refute something that is both such a thing and such a non-thing, and we also refute something that essentially exists as neither. Thus, you should understand that all methods for refuting the tetralemma are like this, involving some qualifier such as “essentially.”

Note that the “qualm” is suggesting that the refutation of the tetralemma leads to nihilism, while Tsongkhapa’s “reply” explains why this suggestion is incorrect. As Tsongkhapa explains, the key to understanding the refutation of the tetralemma is that the tetralemma refers to how things and non-things exist in essential (or intrinsic or inherent) terms. In reality, all things only exist as dependent arisings. In other words, they only dependently exist, but do not intrinsically (or essentially) exist. Neither do they intrinsically (or essentially) exist as non-things. The mode of existence as things or non-things, in intrinsic or essential terms, can all be refuted. Things are empty of inherent (or intrinsic or essential) existence because they are dependently arisen. There are no inherently-existing things or non-things.

The statement that things are not “neither existent nor nonexistent” means that dependently arisen things are outside of this mode of characterization of things being essentially “existent” or “nonexistent,” or essentially “neither existent nor nonexistent.” This is because there is no thing that has essential existence or essential nonexistence, meaning that they do not exist on their own right, or from their own side. All things only exist in dependence on other factors. Their existence depends on their parts, depends on their causes and conditions, and depends on the mind that imputes their label (i.e., their name) onto them. Without this dependence, they do not exist at all.

We must also correctly understand this statement by Tsongkhapa:

Thus, you should understand that all methods for refuting the tetralemma are like this, involving some qualifier such as “essentially.”

It would be a mistake to think that the word “qualifier” here is used to mean the creation of a subset of “existence” and that only this subset is negated. This is NOT the case. The word “qualifier” is to be taken in the sense of a clarification of what is meant, and not as a creator of a subset of existence. When it is stated, as according to Madhyamika philosophy, that “all things lack inherent existence, intrinsic existence, essential existence or true existence,” it means that nothing exists from the side of the object, not even a tiny bit. They are all only dependently arisen. So, in terms of ontology, there is literally nothing left to be negated. It is in this way that all things are completely empty of inherent existence. The qualifier “inherent” here is meant as a “clarification of what is meant” and not as a “creator of a subset of existence.”

In intrinsic or essential terms, to say that a thing is not “existent” means that it is “nonexistent,” and to say that a thing is not “nonexistent” means that it is “existent.” Since things that are only dependently arisen do not fit into this kind of characterization, it is not essentially “neither existent nor nonexistent.” This also explains Tsongkhapa’s words from the “Three Principles of the Path” that tell us that the realization of dependent arising and the realization of emptiness are effectively the same realization. In the words of Tsongkhapa:

Appearances are infallible dependent arisings; emptiness is free of assertions (of inherent existence or nonexistence). As long as these two understandings are seen as separate, one has not yet realized the intent of the Buddha.

When these two realizations are simultaneous and concurrent, from the mere sight of infallible dependent arising comes definite knowledge which completely destroys all modes of mental grasping. At that time, the analysis of the profound view is complete.

The fact that both intrinsic existence and intrinsic nonexistence are not real is also reflected in the words of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra in Eight Thousand Lines (Chapter 1, Verse 13):

What exists not, that non-existence the foolish imagine;

Non-existence as well as existence they fashion.

As dharmic facts, existence and non-existence are both not real.

A Bodhisattva goes forth when wisely he knows this.

It is important to remember here that while it is true that things do not essentially exist, we are not talking about nihilism. Note that Tsongkhapa wrote in the Lam Rim Chen Mo (quoted above) that “we refute the assertion that things essentially exist in terms of both truths [i.e., the ultimate truth and the conventional truth]; however, at the conventional level we do not refute things that can perform functions.” This means that while things do not inherently exist, there is still functionality. The understanding of this is encompassed by what is known as the conventional truth. Tsongkhapa defines conventional truth in this way:

We hold that something exists conventionally (1) if it is known to a conventional consciousness; (2) if no other conventional valid cognition contradicts its being as it is thus known; and (3) if reason that accurately analyses reality—that is, analyses whether something intrinsically exists—does not contradict it.

This last condition needs some clarification. Tsongkhapa points out that rational analysis concerning whether or not something intrinsically exists (or exists from its own side) will reveal that all things are empty of intrinsic existence. However, such an analysis cannot refute conventional appearances and functionality. The analysis was not even looking at this conventional appearances and functionality in the first place. In Tsongkhapa’s words:

When essentialists use rational analysis to refute conventional phenomena such as external objects, reason does not find those conventional phenomena, but it does not contradict them.

Thus, Madhyamika philosophy is not about nihilism. Both the ultimate truth and the conventional truth are correct. Only, one needs to realize the ultimate truth before one can fully comprehend the conventional truth. The best way to express the realization of both, in words, is to state that “all things are empty of inherent existence because they are dependently arisen.” Expressed in this way, we can see that dependent arising occurs even though all things are empty of inherent existence.

As mentioned earlier, one way of understanding “dependent arising” or the conventional truth is that it is akin to what is suggested by the phrase “the interplay of the elements,” only we now have to remove the term “the elements” from the phrase as well. So, it is just the “interplay” without any inherently existing elements involved. That is the nature of the experience of sunyata. That is why our reality, while not actually an illusion, is said to be “like an illusion.”

A realization of the nonduality of existence and nonexistence is important on the spiritual path because this realization is critical to the direct experience of sunyata. Tathata, which is the state of being arising from the realization of sunyata, is often translated as “thatness” or “suchness” because it refers to the realization that what we have before us is simply what it is, without all the artificial discursive elements and elaborations we tend to impute onto things.

As mentioned earlier the experience of sunyata is akin to the experience of henosis described by Plotinus which is sometimes depicted in Western mysticism as a union with the All—a mystical state of nonseparation. In the tradition of Dzogchen (which belongs to the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism), it would be the experience of rigpa, which is the pure awareness that is free of distorting elaborations and artificial embellishments. It is also a direct realization of the Tao which cannot be stated in words since words necessarily involves the use of discursive thinking and elaborations.

______________________________________

As we can see, it is not easy to fully comprehend both the aspects of nonduality discussed above: the nonduality of mind and matter, as well as the nonduality of existence and nonexistence. If we do not first transform our core perspective with regards to the nonduality of self and others, it will be doubly difficult because our mind will tend to reject the very idea that things (especially the self) are empty of inherent existence. That is why we need to transform Hod into Binah (in Yetzirah) before our mind can be receptive to the experiential insight of nonduality that comes from Tiphareth.

Looking at this process in more specific terms, the path from Geburah to Binah (represented in the Tarot by the Chariot) needs to be sufficiently developed before the path from Tiphareth to Binah (represented in the Tarot by the Lovers) can become accesible. This is because if we still perceive the self as an inherently existing entity, we will not be able to accept the fact that all things are empty of inherent existence. This notion of the inherently existing self is generally a very deep-seated idea that we strongly grasp and cling on to. While we are in this state, we will subconsciously reject any notion that things, in general, are empty of inherent existence.

Also, it is important to recognize the difference between a mere intellectual understanding of nonduality and a direct realization of it. It is certainly possible to have an intellectual understanding without a direct realization. Having a direct realization of nonduality means that our entire being is now attuned to its truth and that every aspect of our being (our attitudes, thinking, actions, etc.) are aligned with it. In other words, we have become what it is.

In summary, we can see now that the progression of the spiritual path on this left side of the Tree of Life in Yetzirah corresponds to the progression we had noted earlier in the Tree of Life in Assiyah. The way the corresponding paths interact in the two Worlds of Manifestation thus abides by these words of the hermetic text: “As above, so below.” As we can see in the path diagram, the first stage in this progression is represented by the paths from both Chesed and Hod to Geburah. While the path from Hod (represented by The Hanged Man) transforms our mind through the practice of exchanging self for others, the path from Chesed (represented by Justice) clears the negative karma that would otherwise be an obstacle to a mystical union with the All. Both these processes eventually produce, in the aspirant, a mind that would naturally cease to think in terms of self and others at all, and the path from Geburah to Binah (represented by The Chariot) becomes accessible and this represents the conscious drive to work of the benefit of all without the sense of there being a demarcation between self and others. When this loss of the sense of duality between self and others is sufficiently developed, the path from Tiphareth to Binah (represented by The Lovers) become accessible and we can then gain a deeper experiential realization of non-duality of all phenomena. This comes about because the otherwise powerful tendency to reify the “I” is no longer there to cause us to subconsciously reject any realization that all phenomena are also empty of inherent existence.

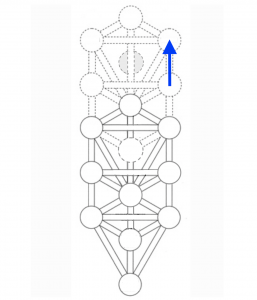

When the two paths from Geburah to Binah, and from Tiphareth to Binah, has sufficiently primed Binah, it will take over as the new Hod in the Tree of Briah, and this Sephirah will be ready to combine with that of Netzach in Briah to open the door to this higher World of Manifestation. Let us now look the paths required to prepare Chokmah to take over as the new Netzach in Briah. The path from Chesed to Chokmah is represented by the Tarot card, The Hierophant:

YETZIRAH: Chesed – Chokmah

Tarot Card: The Hierophant

This path is the result of the combined influences of the path from Netzach to Chesed and that from Tiphareth to Chesed. The path from Netzach to Chesed, represented by the Tarot card, The Wheel of Fortune, is that of how our aspiration to act in accordance with the loss of the sense of self affects Chesed by bringing about a healing of the rifts of karma so that we are more aligned to a condition of oneness with the All. The path from Tiphareth to Chesed, represented by the Tarot card, The Hermit, is one of a meditational aspiration to help all beings by showing the way. When Chesed has been sufficiently primed by the effects of these two paths, the path from Chesed to Chokmah manifests.

This path is represented by the Tarot card, The Hierophant. It is the path that continues after the healing of the transcendent bond with all others. With this deepening sense of unity with all others, a new realization emerges that takes the form of a natural calling that becomes innate to our very nature. It is the dawning of an aspect of our nature that naturally seeks to help all others onto the path to enlightenment, to save all sentient beings from suffering. This characteristic is now infused into our being so that it becomes naturally a part of us. It is in the nature of a calling that is innate in our personality.

Hence, it is represented by The Hierophant—one who leads others and shows them the way on the spiritual path. This state of mind of realizing the need to save all beings from suffering is the result of the deepening of our sense of oneness with all beings. We feel as they feel, and feel their suffering, and so, this need to save them from suffering arises. It is a transformation of our deep and very subtle mind, a transmutation of the innermost depth of our aspiration, towards an alignment with the transcendent oneness of the All. It results in a profound inner calling, now very much a part of our natural aspiration, so that our innermost motivation is one that spontaneously feels the need to save all sentient beings from suffering because of the innate sense of nonseparation with the All.

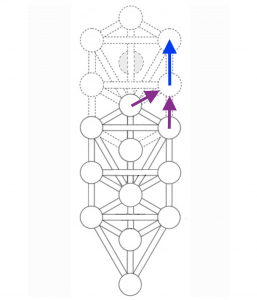

When this path is sufficiently developed, it will draw forth the path from Tiphareth to Chokmah, represented by the Tarot card, The Emperor. It is designated by the Noble Eightfold Path as the path of Right Intention.

YETZIRAH: Tiphareth – Chokmah

Tarot Card: The Emperor

Noble Eightfold Path: Right Intention

This path represents the commitment to lead all sentient beings on the spiritual path towards the state of enlightenment, and to be free from suffering. It is depicted by the Tarot card, The Emperor, because he represents someone who actually leads his subjects towards the goal,and this intention encompasses every one of his subjects without any exception.

It is the ideal, known in Buddhism, as bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is technically the ideal of seeking enlightenment in order to be able to save all sentient beings from suffering. There are two stages to this intention, known as aspiring bodhicitta and engaging bodhicitta. In aspiring bodhicitta, the aspirant wishes to attain enlightenment in order to benefit all sentient beings, but he or she is not prepared to engage in all the practices required for its fulfilment. Engaging bodhicitta, on the other hand, means that the aspirant is now fully prepared to do whatever it takes to achieve this aim.

This path from Tiphareth to Chokmah represents the ideal of engaging bodhichitta, and that is why it requires us to first attain the path from Chesed to Chokmah. That path, represented by The Hierophant, brings about the transformation of our very depth of being into one that has become inseparable with the transcendent All. This, in turn, provides us with the inner conviction that we need to save all sentient beings from suffering. We now feel this need as an innate part of our being. It represents a natural and deep transformation of our innermost motivation to one of helping all sentient beings.

This is the path of engaging Bodhicitta also because it comes from Tiphareth. While aspiring bodhicitta is one where we intellectually desire to fulfill the bodhichitta ideal, here the impetus to act in this compassionate mode comes, not from an intellectual aspiration but from an inner realization that is represented by Tiphareth. Aspiring bodhicitta is like making plans to travel to a destination, while engaging bodhicitta is like actually travelling there

The Noble Eightfold Path depicts this as the path of Right Intention; and the Emperor is an appropriate representation of engaging bodhicitta, which is to save all sentient beings from suffering, not just by showing them the way, but by actually leading them there.

In summary, the process of developing Chokmah—so that it can play the role of Netzach in Briah—is achieved in stages. We need to first develop Chesed through the two paths leading from Netzach and Tiphareth (in Yetzirah). The path from Netzach manifests when we start on the process of aligning our actions in accordance with the loss of the sense of self (represented by the Tarot card, Death, on the path from Netzach to Tiphareth). This path from Netzach to Chesed—represented by the Tarot card, The Wheel of Fortune—is the process of healing the karmic rifts, in our Akashic record, so that we may enter into a more profound state of union with the All. Chesed is also progressively refined via the path from Tiphareth, represented by the Tarot card, The Hermit. Recall that this path, The Hermit, is part of the primary circuit mediated by Tiphareth in Yetzirah, and it represents the progressive build up of the aspiration to help other sentient beings. This progressively primes Chesed until it is ready to bring forth the path upwards to Chokmah.

The path from Chesed to Chokmah represented by the Tarot card, The Hierophant, is the arising of the innate aspiration, from within our inner depths, to save all sentient beings from suffering. It has now become a very part of our nature to seek the salvation of all beings. This then brings forth the path from Tiphareth to Chokmah—represented by the Tarot card, The Emperor—which depicts the firm commitment to do whatever it takes to lead all sentient beings out of suffering. This is the path of Right Intention, the path of engaging bodhicitta.

The process of developing Chokmah, in Yetzirah, follows the same corresponding sequence of processes found in the development of Chokmah in the lower World of Manifestation of Assiyah. Thus it abides by the words of the Hermetic text: “As above, so below.”

When both Binah and Chokmah in Yetzirah have been sufficiently developed to function in the role of Hod and Netzach of the next higher World of Manifestation, we will be ready to open the door to Briah by traversing the path between Chokmah and Binah (of Yetzirah). This is also the process of unveiling the third of the three Veils of Negative Existence, Ain.

Copyright © 2021 by Kenneth K C Chan. All Rights Reserved.